Princes in the Tower

Prince William and Prince Harry lead lives of privilege and comfort, despite the embarrassment that the attention of the media might cause them from time to time. Nowadays, the function of the British monarchy is largely ceremonial, and the House of Windsor is a stable one with no challenges to its succession. These are the reasons that it is probably not too stressful being a member of the Royal family today.

But hundreds of years ago, when the British monarchs wielded real power over their Kingdom, being a member of the Royal family was fraught with danger arising from the sometimes violent and treacherous challenges to the throne. Both the monarch and those next in line had to be wary. The heirs to the throne often had to rely on various factions of nobles for aid and protection, and once they became king it was hard to escape the control of these factions. And sometimes it was hard to figure out who had the best claim to the throne. For instance, the Wars of the Roses in the Fifteenth Century were caused by a dispute between the houses of Lancaster and York over who should be King.

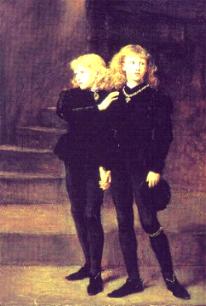

One of the most famous instances of the throne being taken by force concerns the murders of two princes in the Tower of London in 1483. Thanks to Sir Thomas More’s ‘ The History of Richard III’ (1513) and William Shakespeare’s ‘Richard III’ (1592) it is generally believed that Richard III ordered the murders of the princes to eliminate their claims to the throne.

The Princes were Edward, Prince of Wales, and Richard, Duke of York. The death of their father, Edward IV, made the Prince of Wales Edward V. But six weeks later Richard, Duke of Gloucester, claimed that he was King Richard III. The Princes disappeared from their home in the Tower of London in about October 1483, and Richard III was accused of their murders after his death in 1485.

In 1674, workmen found bones beneath a staircase in the Tower. They were buried as belonging to the princes, with an inscription on their gravestone saying that they were murdered by Richard III, usurper to the throne. In 1933 the bones were exhumed and Lawrence Tanner and William Wright declared that as they belonged to children of the right ages, they must be those of the princes.

Nowadays though, the study is rather doubtful and the results probably amount to little. In 1933 forensic science was very primitive, and could not determine the sex of the bones, the cause of death, the century of death, or even whether the owners of the bones were related. The method used to determine the age of the dead children was also unreliable.

Sir Thomas More’s history is also unreliable on a number of counts. He was only seven years old at the time of Richard III’s death. His history contains three accounts of where he believes the bones to be – he does not mention beneath the stairs, where the bones were in fact found.

Most important, he relied on sources that were hostile to Richard III, and he was raised by John Morton, a sympathiser of the new Tudor dynasty. His history, and Shakespeare’s play, were both written while the Tudors were still in power, and both may have been motivated by a desire to flatter the ruling dynasty.

So today it remains uncertain what happened to the princes, whether Richard III was responsible for their deaths, and who the bones belong to. Aside from the biased and inaccurate history of Thomas More and the inconclusive 1933 study, circumstantial evidence points towards Richard’s guilt – he claimed the throne when Prince Edward probably had a stronger claim to it, and the princes disappeared six months into his reign. In any case, the incident is an important illustration of the dangers that went with being an heir to the throne in the past.